History

Six hundred years, through restrictions, the ghetto, emancipation, freedom, fascism and anti-fascism, persecution, the Resistance, and democracy. The Jews of Turin have often played a leading role in the history of the city and Italy.

Chapter 1

The Beginnings

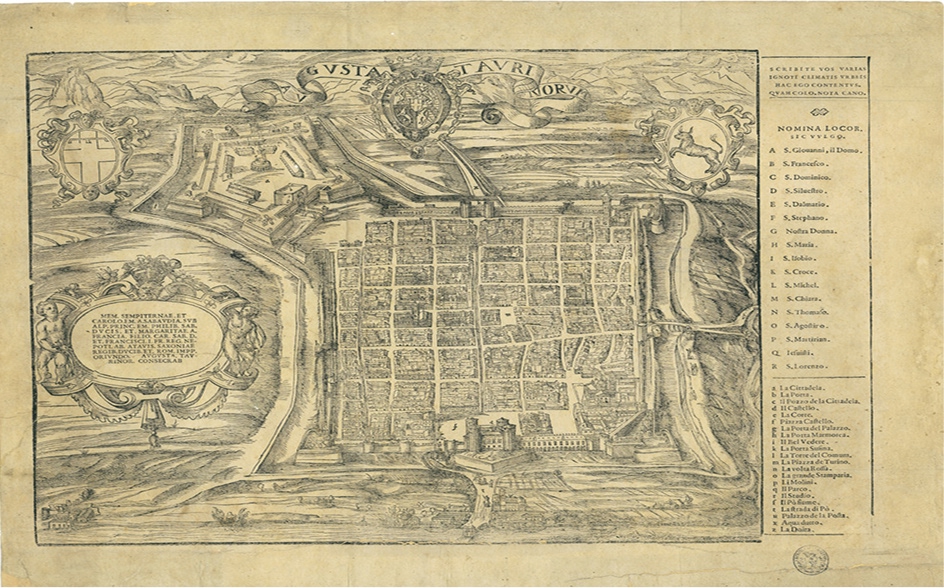

The first confirmed Jewish presence in Piedmont dates back to the early 15th century and appears to be linked to the expulsion of French Jews in 1394. Jews were officially admitted to Turin in 1424; there is no reliable information about the previous centuries, although Bishop Maximus mentioned the presence of Jews as early as the 4th century.

The Statuta Sabaudiae of Amadeus VIII (1430) guaranteed Jews religious freedom but with a strict separation from Christians, the requirement to wear a distinctive yellow sign, and restrictions on synagogues. Unable to own property, Jews were mostly ragpickers, artisans, small traders, and moneylenders; women were often embroiderers.

In the 16th century, many Jews arrived in Piedmont following the expulsion from Spain in 1492. Others came from the coastal regions of southern France, from Provence, and even from Germany.

Chapter 2

The Period of the Ghettos

Over the next three centuries, the Savoy government’s policy toward the Jewish minority fluctuated between greater and lesser severity; at times, tributes were demanded to avoid expulsion.

In 1679, much later than in other Italian cities, the regent Marie Jeanne of Nemours established the actual ghetto, with iron gates that closed from dusk to dawn, between the present-day streets of Maria Vittoria, Bogino, Principe Amedeo, and San Francesco da Paola.

Between the 17th and 18th centuries, Turin’s Jewish population doubled from 750 to 1,500, and the ghetto expanded to the block between what is now Piazza Carlo Emanuele II and Via Des Ambrois, Via San Francesco da Paola, and Via Maria Vittoria. This was still a very limited space, where living conditions were generally very poor.

Chapter 3

Emancipation

The first opening of the ghetto came with the Napoleonic army and the annexation of Piedmont to France: from 1800 to 1814, Jews were able to own property, pursue professions, and attend university. These freedoms ended with the Restoration, but neither the requirement to wear the distinctive sign nor the ban on leaving the ghetto at night returned.

The second emancipation was sanctioned by the Albertine Statute of 1848. The substantial equality of rights allowed Jews to fully participate in the life of the surrounding society, both economically and culturally. Many Turin Jews participated in the Risorgimento movement.

Chapter 4

Between the 19th and 20th Centuries

In the decades following emancipation, the numerous Piedmontese Jewish communities emptied in favor of the capital, and Turin’s Jews increased from just over three thousand to approximately 4,500.

The architect Antonelli was entrusted with the grandiose project for a new synagogue, but in 1875 the Israelite University (as the Jewish community was then called) was forced to abandon the project due to lack of funds, selling the building that would become the Mole Antonelliana to the City of Turin. A less ambitious project was chosen, entrusted to the architect Petiti, on Via S. Pio V (now Piazzetta Primo Levi), in the then-suburban neighborhood of San Salvario; the life of the Community still revolves around the “great temple,” inaugurated in 1884. Since the 19th century, Turin’s Jews have moved to different areas of the city, working in all professions.

Many Jews fought in the First World War, including in command roles.

Chapter 5

Fascism and Anti-Fascism

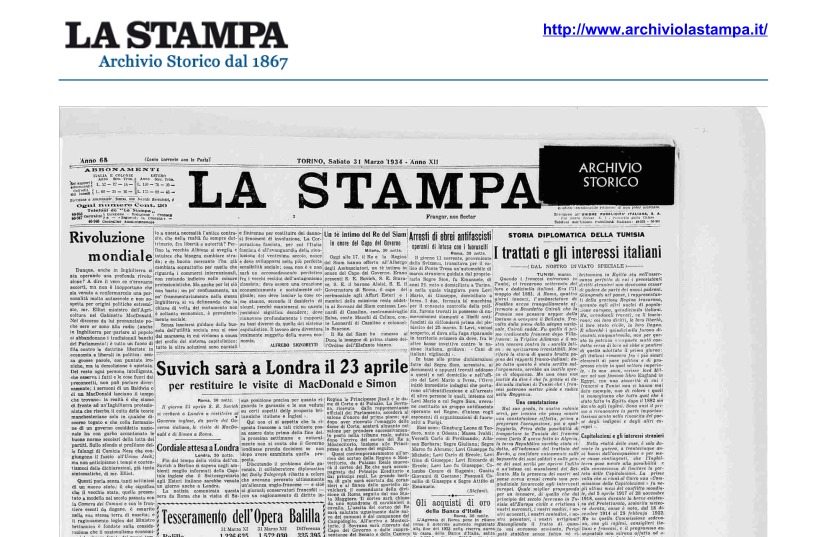

Regarding the fascist regime, Turin’s Jews, as among the rest of Italy, varied greatly, from staunch support to active opposition. Turin’s Judaism distinguished itself in both camps.

Anti-fascist Jews were primarily active in the Communist Party (remember Umberto Terracini, who later became President of the Constituent Assembly, and the brothers Mario and Rita Montagnana) and in the Giustizia e Libertà group, which had a very high Jewish presence (think of Vittorio Foa, Carlo Levi, and Leone Ginzburg).

On the other hand, a fascist Jewish periodical, La nostra bandiera, was published in Turin from 1934 to 1938.

Chapter 6

From the Racial Laws to the Holocaust

With the racial laws of 1938, Jews were barred from many professions, and Jewish students and teachers were expelled from public schools. In Turin, the Jewish elementary school, which had existed for centuries, was joined by a Jewish middle and high school. Many Turin Jews chose to leave Italy.

During the twenty months of the German occupation, Jews were forced into hiding, seeking refuge under false names, or attempting to flee to Switzerland. Many participated in the Resistance; among them, we remember Emanuele Artom, to whom the Jewish middle school is now dedicated. More than four hundred Jews were deported from Turin (eight hundred in Piedmont), of whom very few returned; among them Primo Levi.

Between deportations and emigration, Turin’s Jewish population had shrunk to just over 2,400 by the end of the war.

Chapter 7

The Last 80 Years

Since the end of the Second World War, the number of Turin’s Jews has further decreased: not all those who had been forced to flee because of persecution returned, and others left Turin later, particularly to settle in the newly formed State of Israel. Unlike Rome and Milan, Turin has not seen significant immigration of Jews from other countries.

By the beginning of the 21st century, the Community’s membership had fallen to fewer than a thousand. The Judeo-Piedmontese dialect (i.e., Piedmontese with the addition of some Hebrew words), which was still widely used until the mid-20th century, has almost entirely disappeared.

Despite the significant population decline, Jewish life in Turin has remained vibrant, with many groups, associations, and cultural activities of various kinds. The nursery, elementary, and middle schools remained open despite the Community’s small size thanks to the decision to allow access for everyone, Jews and non-Jews; the same decision was made, in more recent years, for the retirement home.

The participation of Turin’s Jews in the life of the Union of Italian Jewish Communities was significant, as well as in Italian and Turin political life: some Turin Jews have served as members of parliament and city councilors.

Famous Jews of Turin

It’s difficult to list in a few lines all the Jews born or lived in Turin—or in one of the cities that are now sections of the Turin Community—who are known even outside the Jewish world: politicians, entrepreneurs, writers, scientists, artists, anti-fascists, partisans, and many others. We’ll limit ourselves to listing a few of the most well-known.

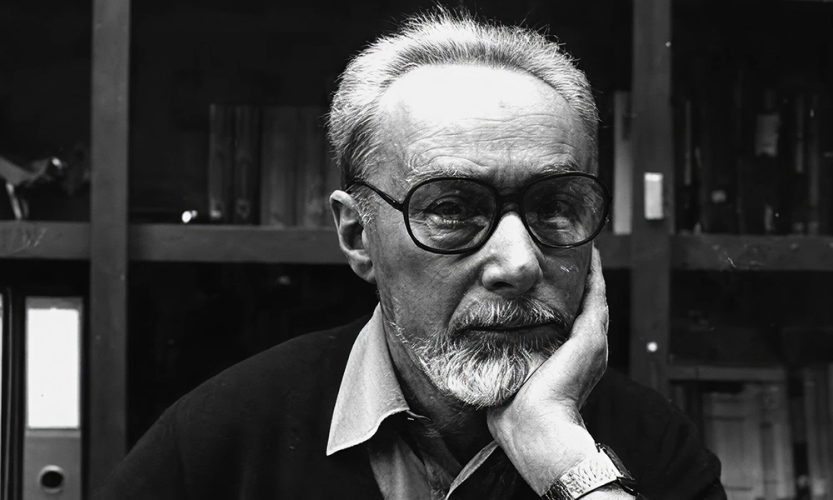

Primo Levi (1919 – 1987)

Returning to Turin in October 1945 after a long journey, recounted in his second book, The Truce, he returned to live in Turin, where he married and had two children. He worked as a chemist, particularly at Siva in Settimo Torinese, where he later became director.

He is the author of a novel, short stories, essays, poems, and articles.

His most famous books, translated into various languages, are read throughout the world.

Umberto Terracini (1895 – 1983)

President of the Constituent Assembly, among the signatories of the Constitution.

Born in Genoa to a family of Piedmontese origin, he lived in Turin after his father’s death (1899) and attended Jewish school.

He was among the founders of the Italian Communist Party. He participated in the partisan republic of Ossola.

Rita Levi Montalcini (1909 – 2012)

Scientist, Nobel Prize winner for Medicine (1986), appointed senator for life in 2001.

Author of popular texts, including In Praise of Imperfection.

From 1946, she lived in the United States for about thirty years.

Carlo Levi (1902 – 1975)

Emanuele Artom (1902 – 1975)

Every year, the Jewish community, along with other schools and institutions in the area, organizes a short march and a ceremony in his memory.

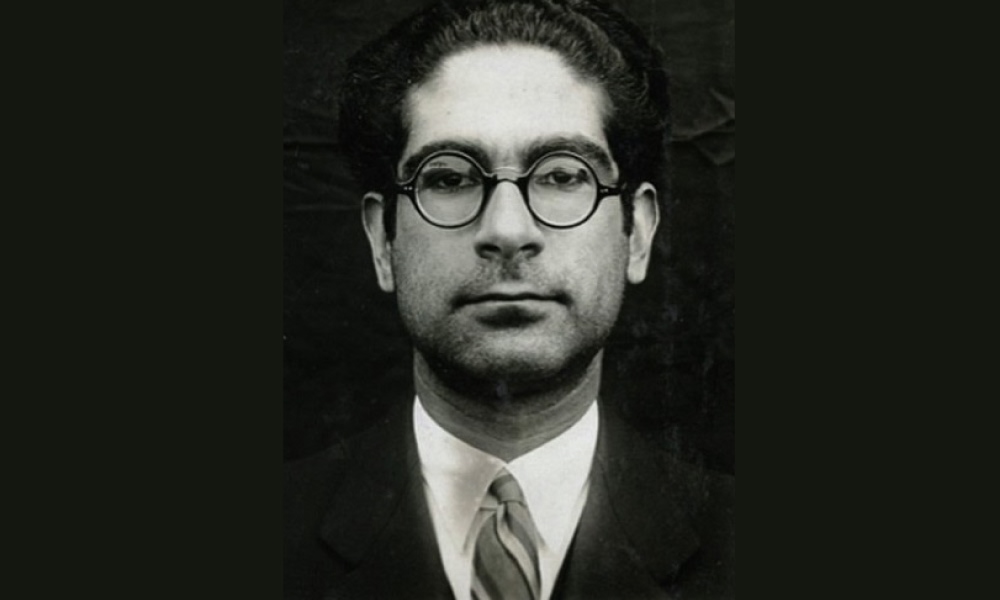

Leone Ginzburg (1909 – 1944)

He joined the Giustizia e Libertà movement. Arrested in 1934, he was released in 1936. In 1940, he was sent into exile in Abruzzo. Released in 1943, he moved to Rome where he participated in the Resistance Arrested, he died in prison as a result of torture. His wife, Natalia, a well-known writer, was of Jewish origin, the daughter of the scientist Giuseppe Levi.

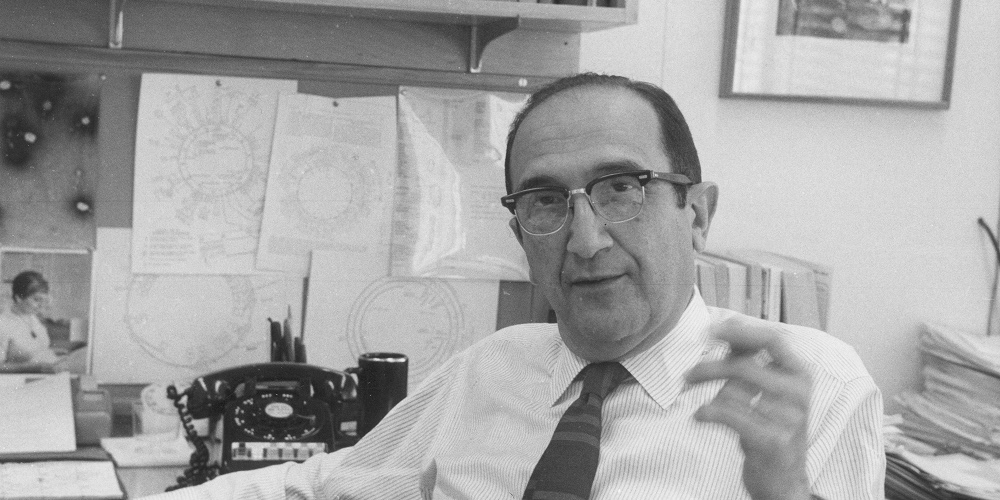

Salvador Edward Luria, nato Salvatore Edoardo Luria (1912-1991)

Nobel Prize in Medicine, 1969. He left Italy following the racial laws of 1938 and moved to the United States.

17:16

17:16 18:26

18:26 Beshallach - Shabbath Shira - Es. 13-17/17-16

Beshallach - Shabbath Shira - Es. 13-17/17-16